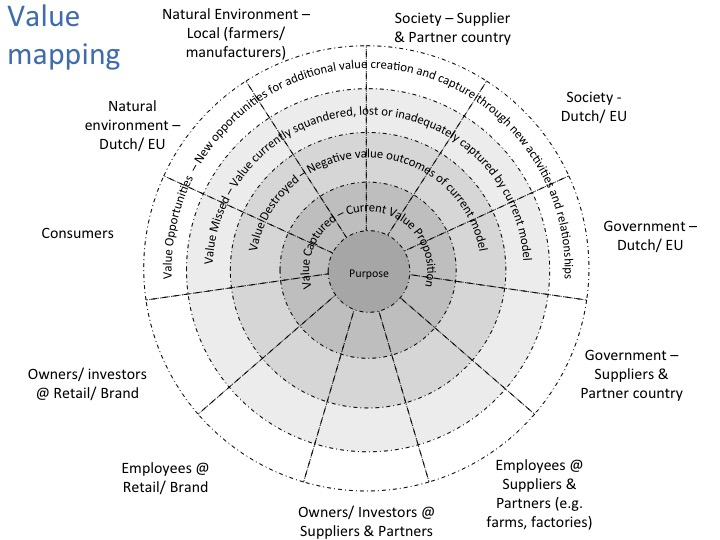

It is often recognised that stakeholder concerns are important for companies’ strategic processes towards sustainability (Bansal, 2005, Stubbs and Cocklin, 2008 and Bocken et al., 2013). Stakeholders are any person(s) or any organisation(s) potentially (directly or indirectly) affected by the operations of the organisation and vice versa (Freeman, 1984). In the value mapping tool for example, Society and Environment, are key stakeholders to take into account in the sustainable innovation process, in addition to the ones that are more familiar to business such as customers, suppliers and owners/ shareholders.

The front-end of eco-innovation, or the early stages of the eco-innovation process, including opportunity identification, opportunity analysis, idea generation, idea selection, concept and technology development (Koen et al., 2001) of eco-innovations is a key stage to start integrating these stakeholder concerns. At later stages of the innovation funnel, it is harder and costlier to change innovations. There are real opportunities in ensuring key stakeholders such as “Society” and “Environment” are integrated early-on into the innovation process. See for example this collection of studies on the business case for sustainability.

This research investigated how stakeholder concerns can be embedded in the from end of the eco-innovation process. This was investigated by running multiple scenarios with innovation teams (students and business) using different tools and approaches at the front end of eco-innovation. Tools such as the value mapping tool and eco-ideation were used with different innovation teams.

It was found that, although trying to integrate a variety of stakeholders in the innovation process is good to enrich the ideas, it can lower the number of relevant ideas generated. Furthermore, visualisation of stakeholder concerns, interests and conflicts is essential to enrich the process. Finally, during the facilitation of such sessions it is important to pay more attention to less familiar stakeholders such as “Environment” and “Society” than to ‘easy’ ones such as “Customers” and “Suppliers”. If easier, participants might imagine certain NGOs as proxies for Society and Environment when they brainstorm about these less familiar stakeholders.

Overall, the integration of multiple stakeholder concerns in the front-end of eco-innovation looks like a promising approach for sustainable innovation.

The full paper is available here.

Sources:

Bansal, P. 2005. Evolving sustainably: a longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strategic Manag. J., 26, pp. 197–218

Bocken, S. Short, P. Rana, S. Evans. 2013. A value mapping tool for sustainable business modelling. Corp. Gov., 13 (5) (2013), pp. 482–497

Freeman, R.E. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pitman Publishing, Bosto

Koen, P., Ajamian, G. Burkart, Clamen, A. et al. 2001. Providing clarity and a common language to the ‘Fuzzy Front End’. Res. Technol. Manag., 44 (2).

Stubbs, W., Cocklin, C. 2008.Conceptualizing a “Sustainability business model”. Organ. Environ., 21 (2) (2008), pp. 103–127

Tyl, B., Valet, F., Bocken, N., Real, M. The integration of a stakeholder perspective into the front end of eco-innovation: a practical approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 108, Part A, Pp. 543–557: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652615010768