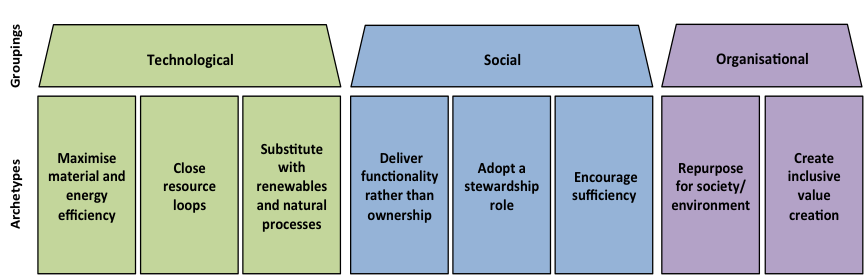

Business models define the way a firm does business. Sustainable business model innovation may be viewed as an important lever for change to ‘business as usual’ to tackle pressing sustainability issues. To expand the scope of business model innovations in practice and research beyond product service systems (e.g. Tukker, 2004), green (FORA, 2010) and social business models (Yunus et al., 2010), sustainable business model archetypes were developed. These include: Maximise material and energy efficiency; Closing resource loops; Substitute with renewables and natural processes; Deliver functionality rather than ownership; Adopt a stewardship role; Encourage sufficiency; Seek inclusive value creation and Re-purpose the business for society/environment (see figure below).

Figure: Sustainable Business Model Archetypes. Adapted from Bocken et al. (2014)

Sufficiency based sustainable business models seek to reduce consumption and, as a result, production. The focus is on influencing consumption behaviour, which may involve product design for durability, a major shift in promotion and sales (e.g. no overselling) and supplier selection based on durability. Profitability would typically result from premium pricing, customer loyalty, and better (particularly more durable) products, while societal and environmental benefits include reuse of products and resources across generations, reductions in product use (impact) and societal education (Bocken et al., 2014). Perhaps the opposite of premium models are ‘frugal innovations’ (or Jugaad innovations) where business model solutions are developed with minimum resource inputs. This may also be viewed as a form of ‘sufficiency’.

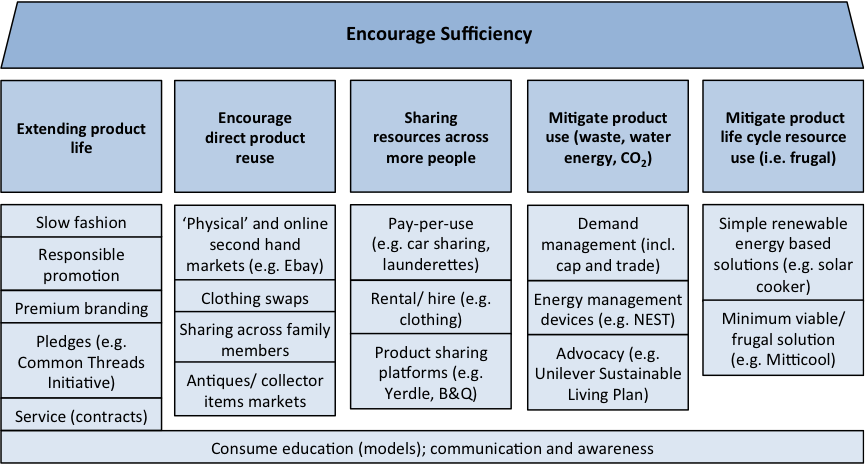

The figure below includes a typology for sufficiency-based business models, which may facilitate the process of building up these business models.

Figure: A sufficiency-based business model typology (Bocken, 2014)

Explanation of the Sufficiency Typology

The examples are briefly explained below:

Extending product life – Ensuring the product will last as long as possible. Characteristics for design: durability, reparability, modular design. The original customer retains ownership of the product. The business model is often ‘premium’ but includes high levels of service.

Encourage direct product reuse – Reuse of the product across markets and generations. After use by one customer, it will be passed on to another ‘customer’ for free or a price mostly lower (except e.g. antiques, collector items) than the original purchase price. Companies such as Ebay facilitate this. A different example of direct product reuse can be seen at Reduse, home of the Unprinter. This start-up (which I support as an advisor) has developed a technology to remove print from paper and make paper reuse possible.

Sharing resources across more people – Sharing the same product across multiple customers. The customer never ‘owns’ the product. Product sharing platforms are emerging to facilitate this.

Mitigate product use – Mitigating the use of energy / resources by individuals and businesses such as demand management by energy providers stimulated by government incentives.

Mitigate product life cycle resource use – Solutions focused on minimising resources, the most prominent example being ‘frugal innovations’. Unfortunately, most of these solutions have been focused on low income countries and have not yet widely expanded to the ‘west’.

References

- Bocken, N.M.P., 2014. Sufficiency based sustainable business model innovation. Sustainability Science Congress, 22-23 October 2014. Copenhagen.

- Bocken, N.M.P., Short, S.W., Rana, P., Evans, S. 2014. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. Journal of Cleaner Production, 65, 42–56

- FORA, 2010. Green business models in the Nordic Region: A key to promote sustainable growth, Denmark. Retrieved http://www.foranet.dk/media/27577/greenpaper_fora_211010.pdf

- Tukker, A., 2004. Eight types of product–service system: eight ways to sustainability? Experiences from SusProNet. Business Strategy and the Environment, 13(4), 246–260.

- Yunus, M., Moingeon, B., Lehmann-Ortega, L., 2010, Building Social Business Models: Lessons from the Grameen Experience, Long Range Planning, 43(2-3), 308–325.